Roger Kizik

Interview

by Lois Tarlow, Art New England, April/May 2000

Lois Tarlow: Tell

me about these book paintings that are hanging about...it's an interesting idea

that the paintings be book shaped; they give a strange illusion of two-and three-dimensions

at the same time.

Roger Kizik: When

books appear in still lifes, the surroundings are often just a pretext to present

the book.

Lois Tarlow: So,

you deleted the setting. When did you do that abstract painting that was in

the [Fuller Museum of Art Ninth] Triennial?

Roger Kizik: About

two years ago. I just finished a similar one. I go back and forth between abstraction

and realism, which must confuse people. They probably think, "What is he

about?" I'm also drawn to things in my life, such as interiors of this

[studio] place. I built it with an eye towards how areas would look in a drawing.

On the other hand, I always have a curiosity for the abstract unknown where

you plunge in and make your own rules or forget about rules altogether. Gerhard

Richter is a good model for going back and forth from abstraction to imagery.

L. T.: The paint

[in your work] is knee-deep. You do them on the floor?

R.K.: Yes, even

the large ones from the seventies and eighties were all done flat. I made a

bridge to kneel on that could move back and forth over the canvas, [and is a

development] in the last four or five years...These have a base of flat, white

latex that I tint with tube colors, because I sometimes want a matte surface

as a foil to the glossy, metallic layer. Working this thick is practical only

for a small size. In the early eighties and early nineties I used squeeze bottles.

I'd mix up about twenty colors and actually draw with them.

L. T.: Some of

these book paintings are conventional rectangles and not book-shaped.

R.K.: I did four

of them from Peterson's book on Mexican birds. I was at the Audubon shop flipping

through some guides and was struck by the vitality...I do books that are personally

significant to me, like the biography of Kafka.

L. T.: Since [they

are] acrylic, you must work quickly, especially when you are incising or squeegeeing

into the paint.

R.K.: It doesn't

have to be done in minutes, but you couldn't leave it for days and come back

and use a squeegee on it. I spray the surface to keep it wet. When it's this

thick, it stays liquid for a while. To freeze the surface and not have blending,

I put a fan on it.

L.T.: Do you ever

use preliminary sketches?

R.K.: I do, but

they get altered in the process.

L.T.: You have

many books and catalogs on artists. Who are your favorites?

R.K.: It's hard

to narrow it down - Morandi, Matisse, Picasso, Stella, Tintoretto. I saw a lot

of Tintorettos on two trips to Venice. With his directness, he was the Manet

of his time. I love the catalog of the Rothko show but was disappointed with

the recent exhibition. The first retrospective, years ago at the Guggenheim,

struck home. But the recent Pollock show held up fabulously.

L.T.: You must

enjoy Manet.

R.K.: Absolutely.

It's his felicitous nature and vitality. He's always probing. He has a perspective

on life that's like a game to him. He came from a bourgeois family, and he's

always style-conscious, but he respected the integrity of the touch and the

act. He always needed a model. He had a poor visual memory...[and although]

he used photo images...he relied on models, even for the Maximilianseries. Not

trusting his own talent, he got soldiers to pose. Somehow, he made great art

out of a lesser talent. It's hard to explain. Her remains accessible in the

way Matisse is accessible. To me, Matisse is like a pottery painter. Picasso's

abilities are really daunting, whereas Matisse is more...down home.

L.T.: Have you

ever had a year off just for your work?

R.K.: I did. I

won three Artists Foundation Grants and with the last one I was able to take

off more than nine months. It was great to be down here day-to-day.

L.T.: You really

look like you belong here.

R.K.: I'm content

to have my roots here - the town, the bay. I travel around the area and always

want to come back here. You can swim in the water, and it's a very forgiving

coastline, not as rugged as Maine, but I like the softness of it.

L.T.: It's serene

here. But your work continues to be explosive

R.K.: Yes, I'm still a conflicted soul. I still have a desire to explore and to be measured by my abstractions, like the one that's drying on the floor.

Roger Kizik

by Carl Belz

From "Visual

Memoirs: Selected Painting and Drawings,"

Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University, 2000

How do I begin

talking about Roger, a friend for 25 years, a colleague at the Rose (Museum)

for 20, a gifted artist always able to surprise, and a person unique in more

ways than I can here begin to inventory? I first visited his studio in 1975.

It was a single room on the second floor of what must once have been, but was

no longer, a humming office building on Pleasant Street in Winthrop. It measured

about 14 feet square, with a 12 foot ceiling, and it was stacked nearly half

full with paintings that were faced to the wall and in every case reached to

just about the full height and width of the space. Which meant that in order

to see the pictures, we together had to drag them one at a time from tone side

of the studio to the other, a challenge to esthetic contemplation that was formidable

in itself and was hardly mitigated by the paintings' considerable weight, the

result of homemade stretchers that were sturdy enough to frame a house. Their

visual rewards, however, turned out to be equally considerable, enough for me

to invite Roger in 1976 to participate in Stepping Out,which became the first

in the museum's series of annual exhibitions devoted to Boston area artists.

He gave me a framed drawing after the opening and wrote n the back, "Thanks

for a show of faith."

A year or so later

I needed to hire a new preparator at the museum, a position whose responsibilities

include installing exhibitions, building crates and frames for paintings in

the collection, organizing the storage vaults, and so forth Normally part-time,

the job becomes full-time during the interval when one show is taken down and

a new one put up and therefore requires a flexible schedule. I thought generally

of artists in that regard, and, remembering Roger's stretchers and the frame

on the drawing he gave me, I thought of him in particular. He was working at

the time as a night custodian at Logan Airport (in Boston), washing floors and

the like, so he gladly accepted when I offered him the job; and that's how we

became colleagues in a situation to which he always brought far more than the

job description required, coming up with inventive ideas for installing shows,

striking signage for the museum's front walls, and exquisitely crafted frames

for our pictures, his taste and intelligence while doing so always impeccable.

Also how he became our "Critic in Residence," as I came to refer to

him, partly because he spent so many nights in the museum, but mostly because

of his remarkable ability to look at the pictures we'd show and articulate their

strengths and weaknesses. That ability made me examine my own tastes so it periodically

annoyed me, but it led at the same time to ongoing conversations about art that

remain memorable and stand as one of my job's most highly valued fringe benefits.

Roger's art has always ranged between the abstract and the representational, because he has always loved art and nature equally, the grand achievements of the New York School on the one hand, the convergence of land and sea and sky on the other. He has regularly found the former in visits to galleries and museums in the Big Apple, and he has regularly found the latter down off The Cape, which is where Great Island Bar,was inspired during a day of sailing in 1985. It must have been a very special day sitting there at the tiller, for the painting is everywhere luminous and warm, liquid and sensuous, putting us in intimate pictorial touch with a firsthand experience that we're convinced was just as intimate for the artist, and certainly worth remembering.

Power in Numbers

Nielsen and Krakow Deliver Summer Heat

by Christopher

Millis

"Summer Surprises"

At Nielsen Gallery, 179 Newbury Street, through August 30, 2003

With a show title like "Summer Surprises" (why not "Paintings

on Walls" or "Art Worth Buying"?) and a virtual armada of watercolor

boats that greet your entrance, you don’t have to be a cynic to be skeptical

of what’s in store at Nielsen Gallery this month. Marine imagery in the

Back Bay during tourist season is not the stuff of which exciting exhibits are

made, right?

Wrong. Despite

the enervated title and the immense improbability of interesting frigates, "Summer

Surprises" lives up to its name: it’s bright, as in smart and lively,

it’s packed with what you’d never expect, and it’s fun. Let your

prejudices set sail.

As for those boats:

I counted eight altogether, and they make up half of Roger Kizik’s 16 small

(7x11), delightful watercolors. The energy and good humor of his shimmering,

playful, quotidian images — campers, beer bottles, bugs, goggles, the occasional

house — is conveyed so matter-of-factly, you scarcely notice how astute

he is. I’m no fan of product placement — the brand-name candy so prominently

ingested in E.T., or the full-frontal label of the beverage at the beginning

of the latest Terminator — so I had to work at figuring out why I wasn’t

at all put off by the Corona beer bottle that towers at the center of Waiting

for the Tide. Part of the answer turns out to be that it does tower: the beer

bottle dwarfs the motor yacht to its right and the SUV to its left. It’s

as if the artist were implying that booze fuels both. Further, the bottle’s

been integrated into the scene, and not just as a monolith — Kizik could

have called the piece Size Matters for the way the three objects compete for

our attention. The surrounding sky boasts the color of the beer; the black of

its label appears nearby and is identical to the shadows cast by the two vehicles.

You can’t tell whether the work’s meant to be a putdown or a party,

but in neither case is it a commercial.

Kizik’s incorporation

of name brands — Wilson tennis balls at rest on a racket, a matchbox labeled

"New York Yacht Club" — in no way resembles Andy Warhol’s

fiercely casual meditations on the banality of commercialism. Rather, it reads

like a Whitman poem: the bountiful detritus of daily life isn’t abstract,

it’s got logos. A giant green beetle, fully half the size of the Scubapro

goggles it’s ambling toward along the sand, turns out to be the only living

creature in any of these frames. Perhaps the product labels have taken over

for the humans.

If Kizik’s dense, tumultuous compositions have an opposite, it would have to be the sparse, hushed landscapes of Mel Pekarsky, whose shadowy pencil, oil, and pencil-and-oil renderings of low-lying desert shrubs and stones against white, sandy expanses convey the desert’s charged sense of unseen presence. For all its quietude, Dry Season achieves a kind of momentum as the concentration of flora gradually increases from open spaces to a thick network of bushes and weeds. The perspective is aerial and ambiguous — it could be a flying bird’s, it could be a walking human’s. The artist makes you feel an urgency to take it all in — in a moment you’ll be gone and it will disappear.

Friday June 1, 2007

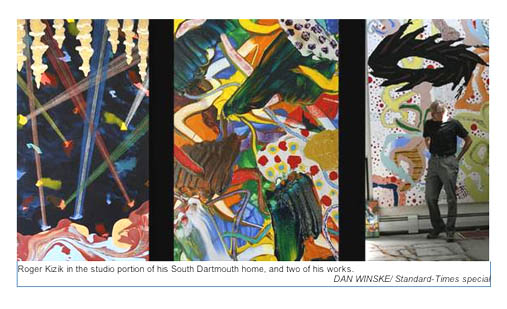

Roger Kizik imbues 'open-ended' abstracts with playful artistry

by DAN WINSKE/ New Bedford Standard-Times special

Children are often big fans of Roger Kizik's colorful abstract paintings, and the Dartmouth artist says that's fine with him.

His larger-than-life canvases, sometimes 8 feel high, are filled with dancing, swirling, zigzagging bursts of color that are poured, squirted or dripped onto the surface. Mr. Kizik uses the word "whimsical" to describe his work, and it is this sense of playfulness with color and shape that appeals to the childlike imagination of his viewers of all ages.

Mr. Kizik, 61, grew up in Medford, where his father ran a sausage factory and played saxophone in a successful dance band. Mr. Kizik was introduced to art as a child during visits to his aunt, who lived on Fifth Avenue and took him to see New York City museums. He also accompanied his mother on Saturday afternoon trips to the DeCordova Museum in Lincoln, where he was most impressed with the abstract works.

The teenage Roger drew and painted with dedication while in high school, then decided to join the Navy when he graduated in 1964. He spent his leave time visiting galleries and museums in Boston, Philadelphia and New York City. The abstract masters — Picasso, Matisse, Pollock and Rothko — inspired him with their power and audacity.

ROGER KIZIK'S FAVORITE THINGS

Books: "Ulysses" by James Joyce, "The English Patient" by Michael Ondaatje, "Paul Cezanne, Letters" edited by John Rewald.

Music: Tenor saxophone jazzman Coleman Hawkins, 1904-69.

Favorite movies: "Shoot the Piano Player," 1960; "Cinema Paradiso," 1989; "Babel," 2006.

Favorite artists: Picasso, Giorgio Morandi, Edward Hopper, Henri Matisse, Paul Klee, Gerhard Richter.

Hobbies: Tennis, hockey, biking, kayaking.